Starbur (Acanthospermum): A Weedy Wildcard You’ll Want to Recognize

If you’ve ever walked through a field or vacant lot in the warmer parts of North America and found your socks covered in tiny, star-shaped burrs, you’ve likely made the acquaintance of starbur. This small but mighty plant has a knack for getting around – literally sticking to anything that passes by.

What Exactly Is Starbur?

Starbur (Acanthospermum) is a low-growing forb that’s part of the sunflower family. Don’t let the family connection fool you though – this isn’t the kind of plant you’d want stealing the spotlight in your flower garden. As a forb, it’s an herbaceous plant without woody stems, meaning it stays relatively soft and green throughout its growing season.

This plant can be either annual or perennial depending on the climate, which gives it impressive staying power in areas where it takes hold.

Where Does Starbur Call Home?

Here’s where things get interesting: starbur is native to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, but it’s become quite the traveler. This non-native species has established itself across much of the southeastern United States and beyond, currently found in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and even as far north as Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. It’s also made its way to Hawaii, Oregon, and parts of Canada.

Should You Plant Starbur in Your Garden?

The short answer? Probably not. While starbur isn’t officially classified as invasive everywhere it grows, it definitely behaves like a plant that doesn’t need any encouragement. Here’s why most gardeners will want to skip this one:

- It produces those infamous spiny burrs that stick to everything

- It tends to spread aggressively in disturbed soils

- It offers limited ornamental value compared to native alternatives

- It can crowd out more desirable native plants

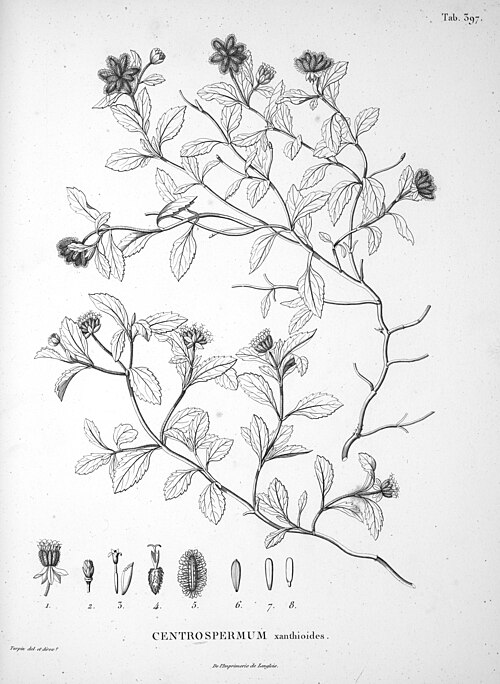

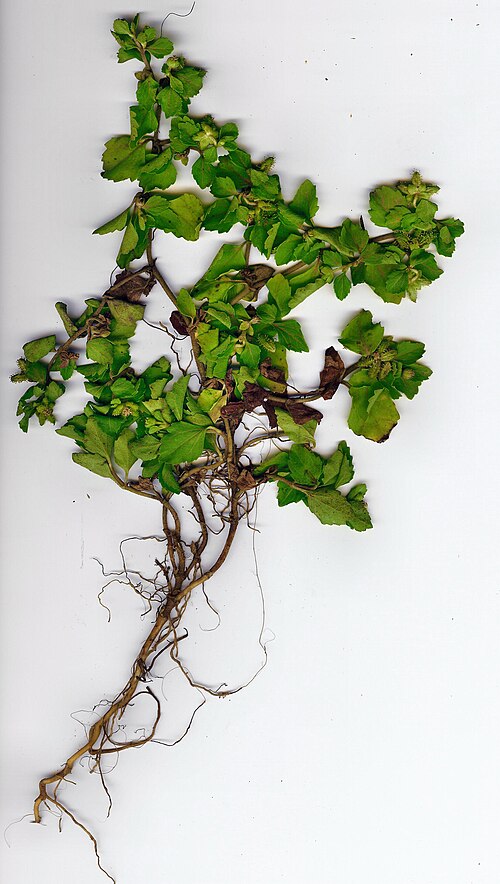

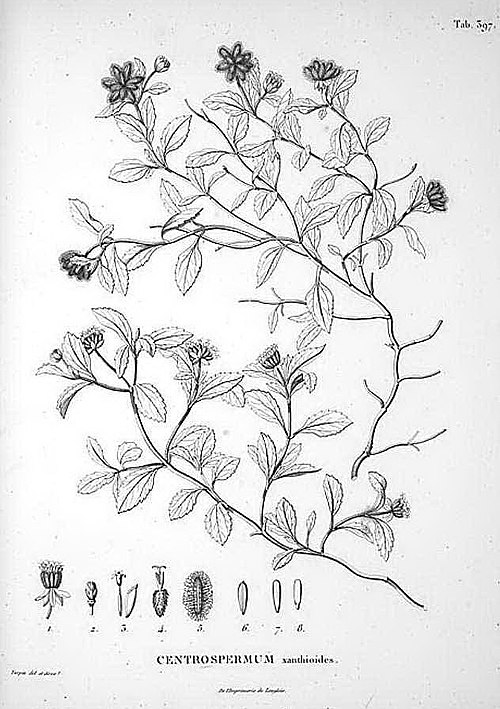

What Does Starbur Look Like?

Recognizing starbur is pretty straightforward once you know what to look for. It produces small, yellow flowers that might remind you of tiny sunflowers – again, that family resemblance showing through. But the real identifying feature is those distinctive star-shaped seed heads covered in spines. These burrs are nature’s version of velcro and are incredibly effective at hitching rides on clothing, fur, and feathers.

The plant itself stays relatively low to the ground and has a somewhat sprawling growth habit.

Growing Conditions (If You Must Know)

Starbur is remarkably unfussy about where it grows, which partly explains its success as a colonizer. It thrives in:

- Full sun locations

- Disturbed soils

- USDA hardiness zones 8-11

- Areas with warm, humid climates

The plant is quite drought-tolerant once established and seems to particularly enjoy areas where the soil has been disturbed – roadsides, construction sites, and neglected garden edges.

Better Native Alternatives

Instead of encouraging starbur, consider these native alternatives that offer similar resilience but with better garden manners and wildlife benefits:

- Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia species) – Bright yellow flowers, excellent for pollinators

- Lanceleaf Coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata) – Cheerful yellow blooms, native across much of North America

- Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) – Great for pollinators and has aromatic foliage

Managing Starbur in Your Landscape

If starbur has already made itself at home in your yard, the best approach is to remove it before it sets seed. Hand-pulling works well for small patches, especially when the soil is moist. For larger infestations, mowing before seed set can help reduce spread, though you’ll likely need to repeat this process.

The key is persistence – don’t let those burrs mature and disperse if you can help it.

The Bottom Line

While starbur might not be the garden villain that some invasive species are, it’s definitely not a plant that needs any encouragement from gardeners. Its aggressive spreading habit and limited ornamental value make it a poor choice for intentional landscaping. Instead, focus on native alternatives that will provide better benefits for local wildlife while behaving more predictably in your garden space.

Remember, the best gardens work with nature, not against it – and sometimes that means saying thanks, but no thanks to plants that are a little too good at making themselves at home.