Jointed Goatgrass: Why This Non-Native Grass Should Stay Out of Your Garden

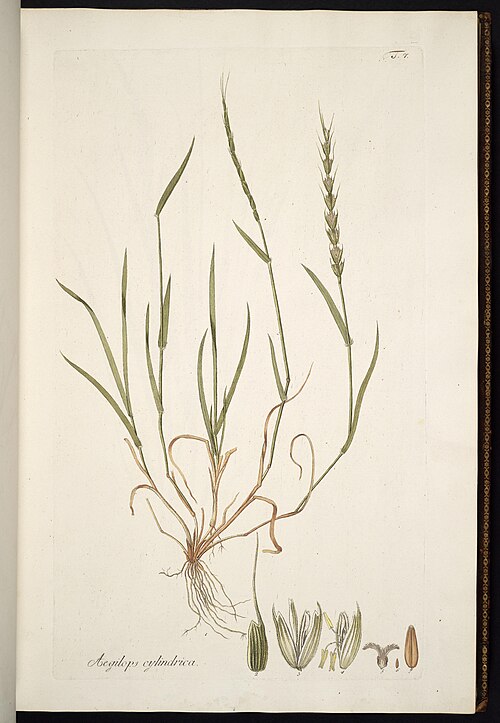

If you’ve stumbled across the name jointed goatgrass while researching grasses for your landscape, you might want to keep scrolling. While this annual grass (scientifically known as Aegilops cylindrica) might seem like just another grass option, it’s actually a problematic non-native species that’s better left out of intentional garden plantings.

What is Jointed Goatgrass?

Jointed goatgrass is an annual graminoid – that’s fancy talk for a grass-like plant. Originally from the Mediterranean region and southwestern Asia, this hardy little troublemaker has made itself quite at home across much of the United States, despite not being invited to the party.

You might also encounter this plant under several scientific synonyms, including Cylindropyrum cylindricum and Triticum cylindricum, but don’t let the fancy names fool you – it’s still the same weedy character.

Where You’ll Find It (Whether You Want To or Not)

Jointed goatgrass has spread its influence across an impressive 32 states, from Alabama to Wyoming. It’s established populations in Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Why Gardeners Should Think Twice

Here’s the thing about jointed goatgrass – it’s not exactly what you’d call a garden beauty. This annual grass lacks the ornamental appeal that most gardeners seek, and its claim to fame is more about being a persistent agricultural weed than a landscape asset.

As a non-native species that reproduces spontaneously and tends to persist without human help, jointed goatgrass falls into that category of plants that are better admired from afar (if at all). It’s particularly problematic in wheat-growing regions, where it can cross-pollinate with crops and create headaches for farmers.

Growing Conditions (For Identification Purposes)

If you’re trying to identify jointed goatgrass on your property, it typically thrives in:

- Disturbed soils

- Roadsides and waste areas

- Agricultural fields

- Areas with poor soil conditions

This adaptable grass can handle USDA hardiness zones 4-9, which partly explains its wide distribution across the country.

Better Alternatives for Your Garden

Instead of jointed goatgrass, consider these beautiful native grass alternatives that will actually enhance your landscape:

- Buffalo grass (Bouteloua dactyloides) for drought-tolerant lawns

- Little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) for ornamental appeal

- Blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) for xeriscaping

- Prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis) for fragrance and texture

The Bottom Line

While jointed goatgrass might be hardy and adaptable, these aren’t always virtues in the gardening world. Its non-native status, weedy nature, and lack of ornamental value make it a poor choice for intentional cultivation. Instead, embrace the beauty and ecological benefits of native grasses that will support local wildlife and complement your regional landscape.

Remember, the best gardens work with nature, not against it – and that means choosing plants that belong in your local ecosystem rather than those that might outcompete them.